Narrative design is a specialised form of design that is today necessary in producing both commercial and applied games, whether in using the medium of video games, board games, VR installations, escape rooms, or others.

I have been working with, researching, and occasionally teaching narrative design in the last few years, and I kept reading and experimenting with the complex relationship between story and game mechanics in video games. Let’s try to define narrative design and provide examples of this specialized kind of work.

What is Narrative Design?

It is not easy and actually not that necessary to distinguish precisely between game design, game writing, and narrative design. Still, operationally, it can turn out to be a useful distinction to be aware of.

In a book dedicated to narrative design, Narrative Design for Writers: An industry guide to writing for video games the author defines narrative design as follows:

A game writer produces all the narrative bits that a player will see and hear within the game. Dialogues, flavor texts, diaries… basically any kind of in-game text or voice over. A narrative designer does the higher level stuff like storylines, world building, lore development, character creation… all the background material that forges a story context for the player. [...] Narrative design is about using Story to ensure that Play has Meaning.

McRae, Edwin. Narrative Design for Writers: An industry guide to writing for video games (p. 3, 6). Fiction Engine Limited. Kindle Edition.

Let's now see how Hannah Nicklin, in the reference book for game writing, Writing for Games distinguishes between game writing and narrative design:

Narrative Design Is Not Writing and Vice Versa

Writing is not narrative design, and narrative design is not writing. [...] Narrative design is the practice of game design with story at its heart. You are the advocate for the story in the design of the game. Narrative is (and we will dig down more into this in the next chapter) the design of the telling of a story. Not just a plot in a world with characters, but also the decisions around in what order the plot is communicated, how characters and the environment build together, structure, pacing, choice design, voice, perspective, role-play relationships, UI, the key decisions around tools, player agency, and much else. It is storytelling through design.

Nicklin, Hannah. Writing for Games (p. 23). CRC Press. Kindle Edition.

One way I could define narrative design is the following. A narrative designer is someone capable of answering this kind of question: how to compose and support dialogue and interaction direction while defining a parametrical and perhaps partially generative branching narrative? How do we define and support character evolution? Technically, how can we support a practical, feasible context for localisation and debugging as a narrative designer? You must work with a mix of contents, parameter values and direction notes. And crucially, must know how to work with game writers and mechanics developers in a production/release loop.

Looking at the problems from a more technical perspective, I could define narrative design as defining rules for each subset of each ticking loop (a status check of the story system) or sequence that creates the story for the player; this theme of detailing narrative design will be dealt with in a dedicated exercise booklet I’m working on, later more on that.

I think that you probably got the idea as an operationally helpful definition.

The widening scope of narrative design

Game designers and developers have become progressively more aware of the usefulness of specifically narrative design for a broad spectrum of games, beyond games whose main classification is “narrative” or have a significant amount of textual content.

“That’s when narrative design becomes more closely related to theme park design or interior design than to writing films or novels. You’re creating an experience to enjoy, not a plot to follow.”

McRae, Edwin. Narrative Design for Writers: An industry guide to writing for video games (p. 5). Fiction Engine Limited. Kindle Edition.

This broadening is also due to the evolution of games, where it is now customarily expected to integrate narrative and mechanics in every dimension.

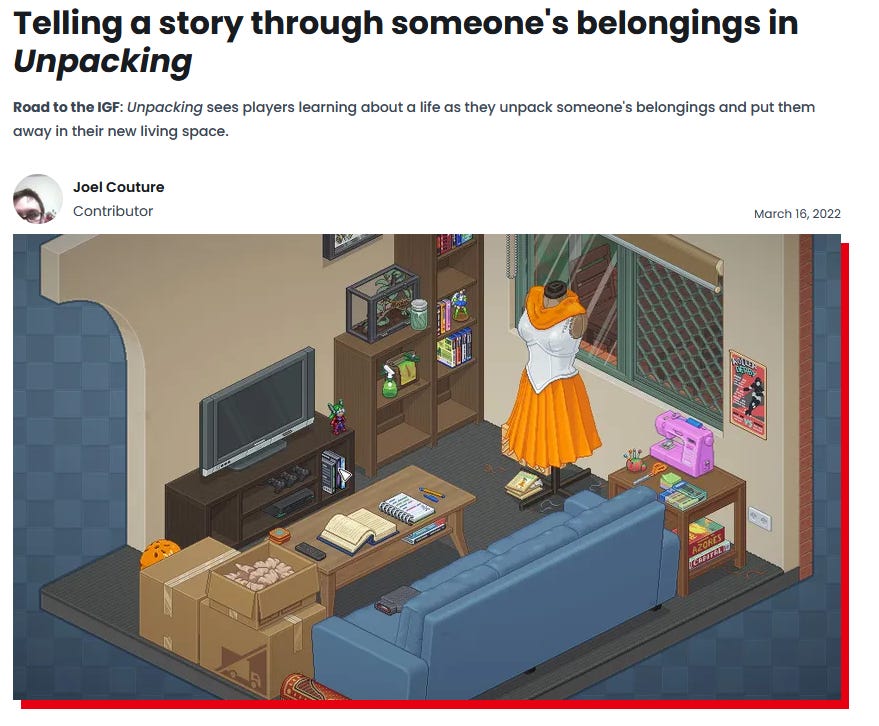

A helpful example of a game with little text and a lot of narrative design is the game Unpacking, which is a game with no text, but has a well-defined narrative that the player experiences: considerable narrative design was needed to make this game.

Narrative design can be a secondary dimension that works quietly in the background of the game mechanics. Narrative design is technical work that weaves story, mechanics, and plot together.

Let’s now see some notes on the narrative design of the applied and then the three commercial games I have been and am working on.

30 applied games

I started designing games ten years ago, mostly applied games, and I have always tried to curate their narrative content. The general principle I follow in working in applied games (games for health, social issues, education, communication) is “diegetic connectivity”, here there is an introductory paper. So, it has been a playground to experiment with narrative design with limited means but dealing with a variety of topics. You can find several applied games presented and sometimes playable on Open Lab’s website.

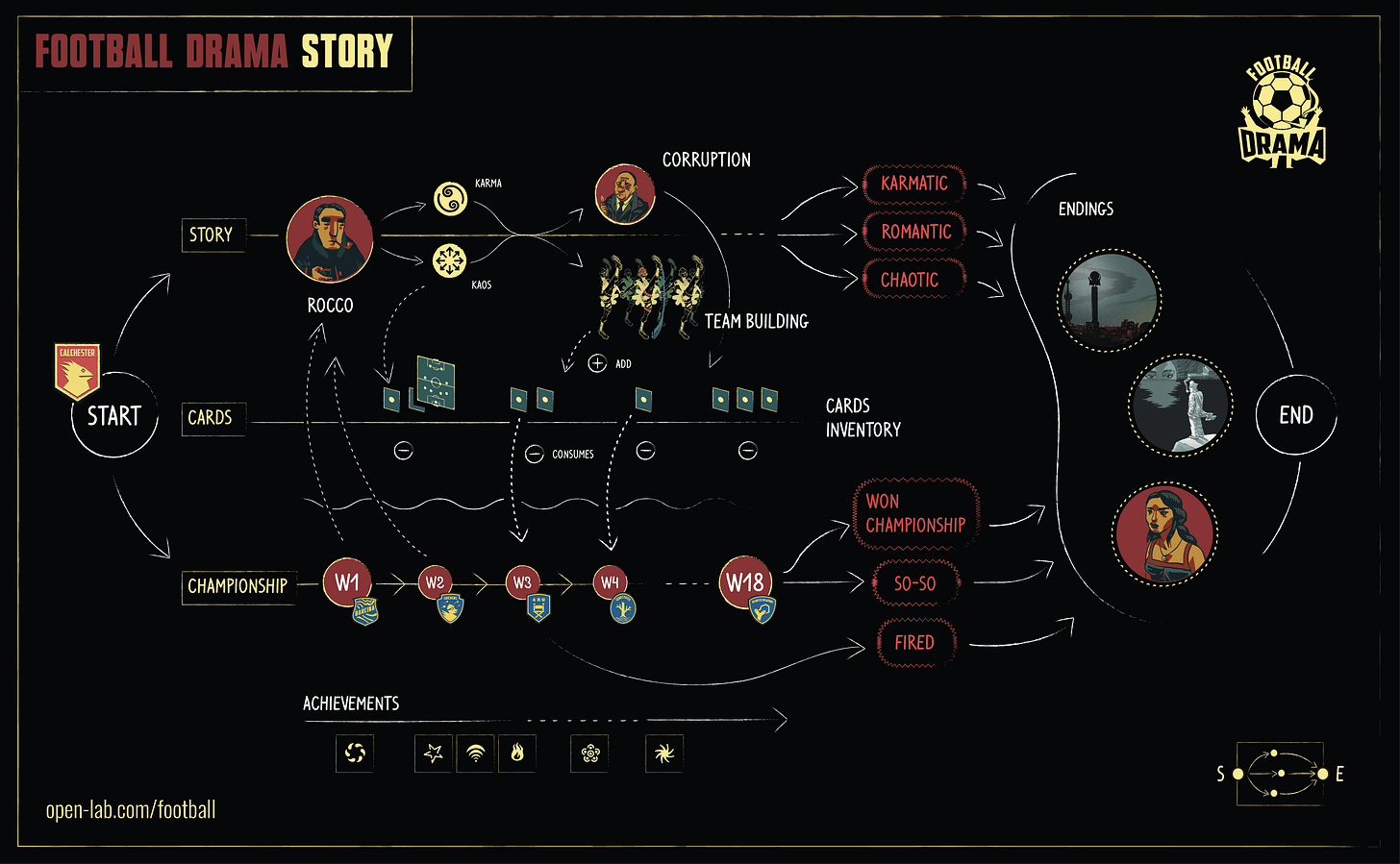

Football Drama

I wrote extensively about the design work done for Football Drama in 2019 here:

There is a natural attrition between branching narrative and mechanical design, and in the case of a championship, that can go many ways there is the problem of syncing results with an evolving plot, that in my case was not directly determined by the sport results: again, here a lot of narrative design work is needed. You can play the game here.

Roller Drama

For Roller Drama, we did a lot of work on further refining the UI design of the dialogues, with direction, effects, and emotional representation.

See this old post by Daniele Giardini and myself, Videogame Dialogues: Writing Tools And Design Ideas, which gave the initial inspiration.

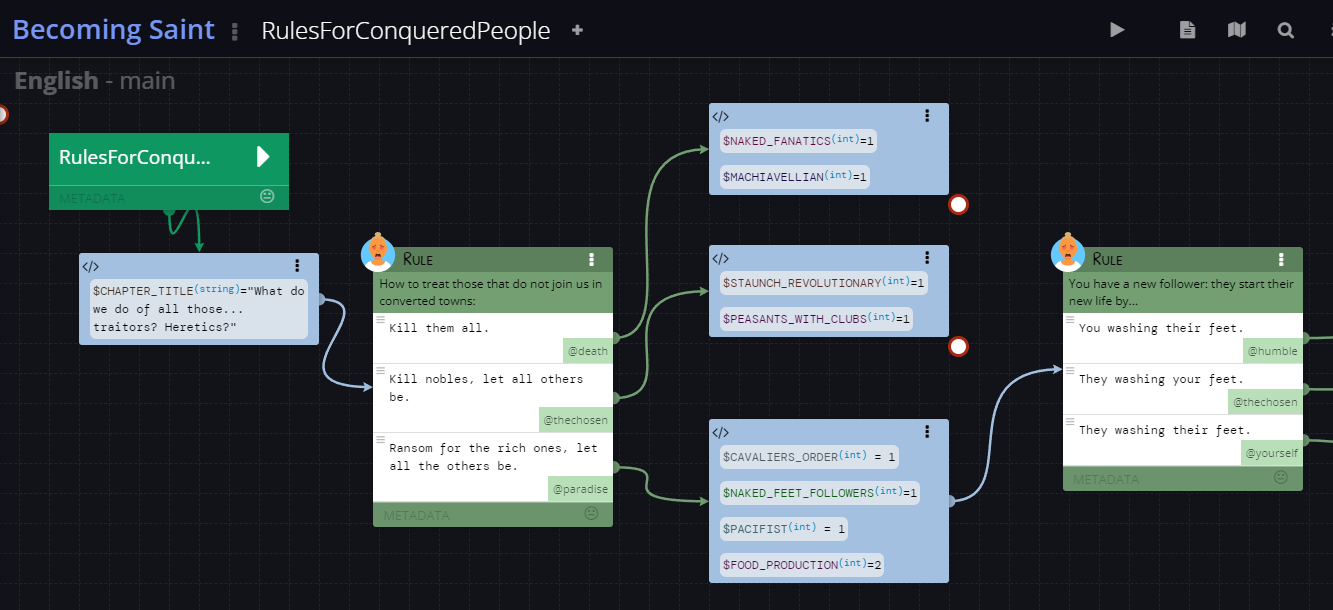

Becoming Saint

In Becoming Saint, there is a lot of game and narrative design, and little game writing, as compared to the previous two experiences. However, the narrative content is quite parametrically structured and defines the core rules that determine who follows you and how your followers can survive.

You define your creed progressively through choices, and later in the game, you have to make decisions when faced with new historical events, like the death of the Pope or the emperor.

In this post, I have outlined the idea of “historic game” that is behind this project.

Narrative design tools and exercises

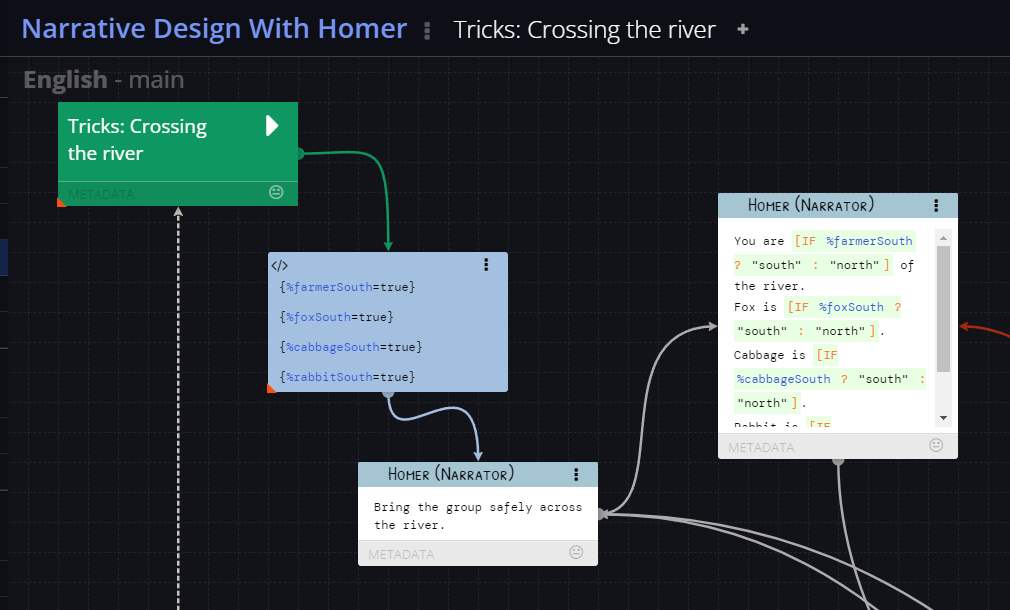

Inspired by the beautiful and powerful narrative Unity module Outspoken by Daniele Giardini and also considering the features of Inkle’s Ink, with Matteo “pupunzi” Bicocchi we have released our own free web-based tool, Homer, which you can freely use.

It supports both writing content and designing narrative logic, and I have been using it for all my projects.

The Narrative Design Toolbox

So all this research and game production and development is getting collected and exemplified in a structured set of examples and exercises, which will form a short exercise book; and lo and behold, I now have a companion author, Matteo Pozzi, the well-known game designer and writer from the We Are Muesli duo.

So if you want to keep informed about this topic, subscribe to my Substack or follow me on (X)Twitter.

P.S. This is a very cool talk on A Narrative Approach to Level Design.